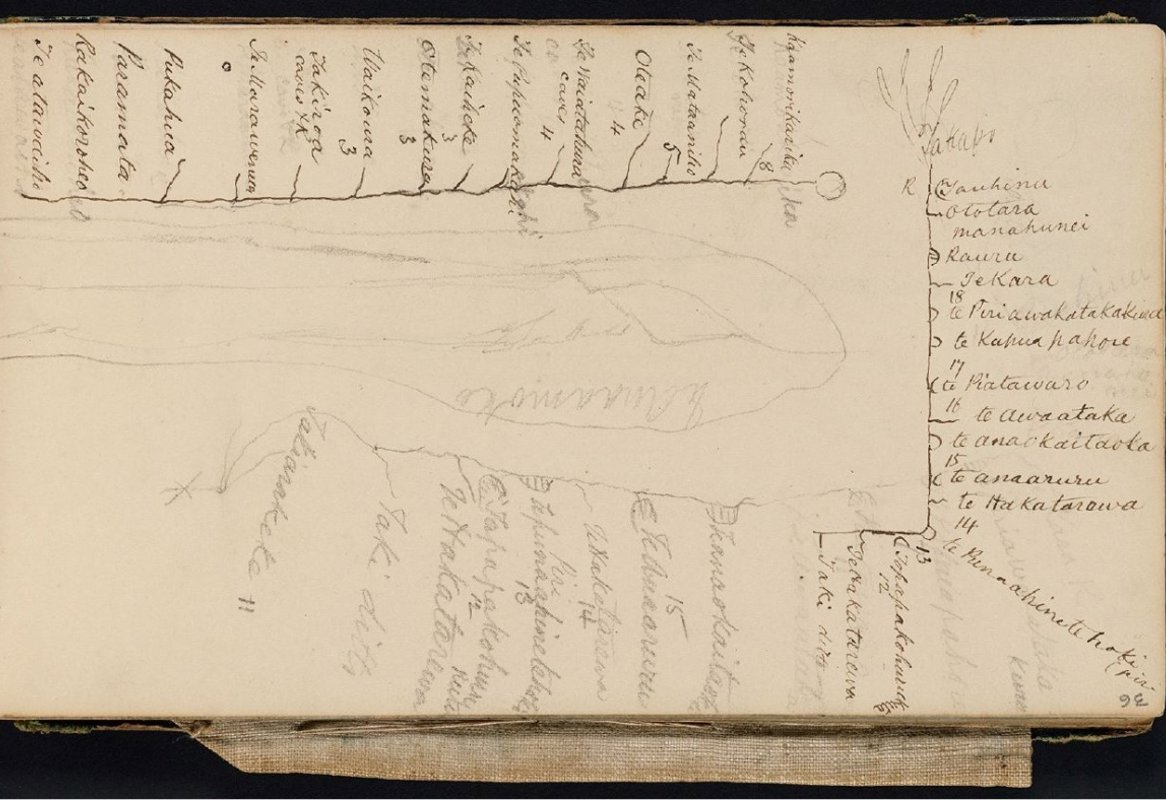

From the mouth of the Waitaki, people followed the awa (river) to where Lake Benmore now stands. They would either advance along the Ahuriri River and over Ōmakō (Lindis Pass) into the Central Otago region, or continue to follow the Upper Waitaki into Te Manahuna. Upon arriving at Te Manahuna, the Ōhau, Pūkaki and Takapō Rivers could be followed to their respective lakes and catchments.

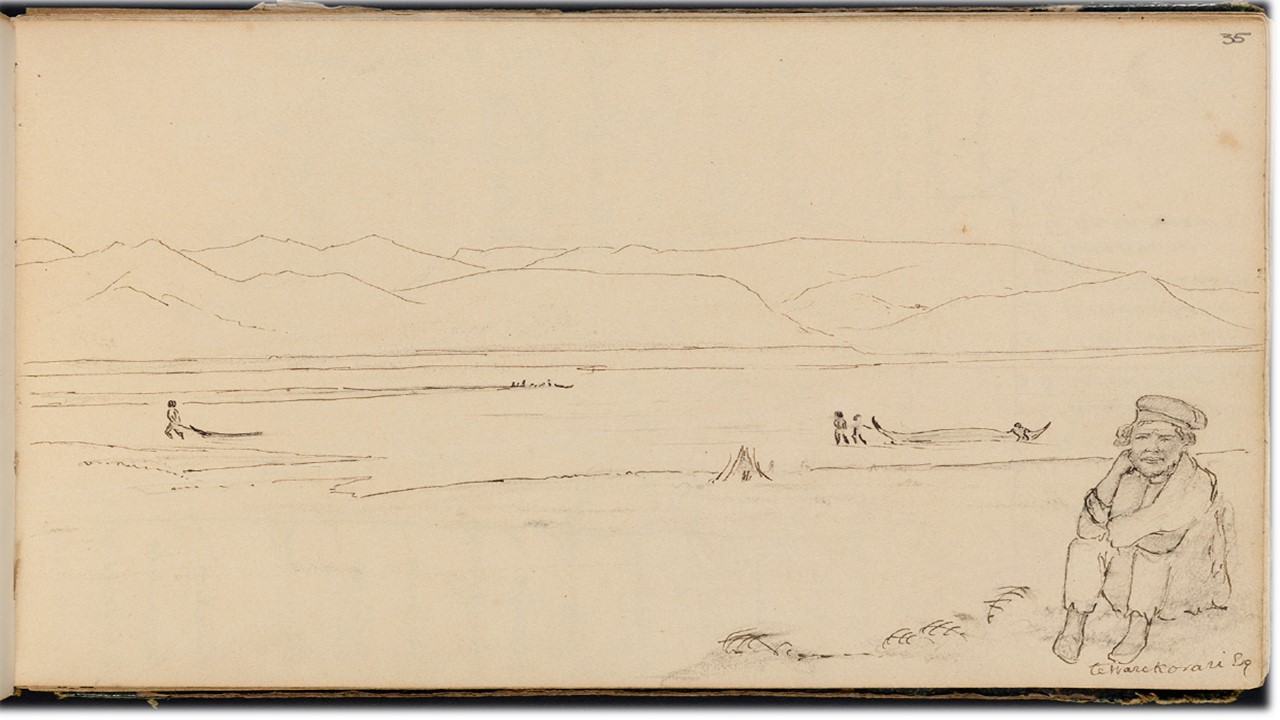

The traditional mode of transport on the Waitaki was mōkihi (raft-like vessels, constructed from raupō). Mōkihi enabled the resources gathered in the hinterland to be transported back to the coastal kāika with comparative ease. People walked up the Waitaki to gather mahika kai, and then used mōkihi to transport the resources back down the awa. Weka were gathered primarily during autumn and winter, when the fat content was at its highest, to be preserved for the colder months. The last recorded harvest of weka in Te Manahuna was in 1870, when three tonnes of birds were taken. Mōkihi were eventually replaced by horse and cart later in the nineteenth century.

The creation of lakes Benmore and Aviemore in the 1960s, as part of the Waitaki hydroelectric power scheme, flooded parts of the old trail; submerging most of the known rock art sites in the Upper Waitaki Valley, as well as several traditional kāika mahika kai.